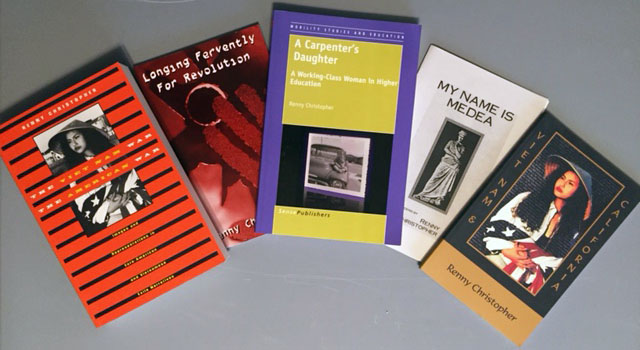

Longing Fervently for Revolution: Upward Mobility and Its Discontents

Winner of the 1998 Slipstream Press Poetry Chapbook Competition

"Renny Christopher's poetry demonstrates that poetry can be a powerful access to understanding: her poems allow working-class people to feel visible and respected in a genre that usually ignores or objectifies them." --Carolyn Whitson, Metropolitan State University

May 4, 1970

In my first year of high school

my friends already talked

of marriage and children.

When they did I put my hands

over my ears.

A teacher told me

I'd never get a husband

if I didn't stop answering

all of the questions in class.

My friends talked of work.

I had no talent, like my mom,

for fixing hair.

And I was

too clumsy for a waitress

too sarcastic for a store clerk

too selfish for a nurse

too impatient for a factory line.

I was smart,

so I could be a secretary.

But restlessness ran in my veins--

I crossed my arms, clamped my jaw

and refused to learn how to type.

I didn't know what to dream of,

so I watched the news,

looking for a clue.

I wanted to see those places far from here

where there were wars.

I yearned for the rifle in my hands

but had to settle for shooting beebees

at popsicle sticks in the creek

while dreaming of being a boy,

joining the marines.

The TV seemed the only window

out of the living room walls.

My mother walked back and forth

while cooking dinner.

She paused

her worn hand resting

on the back of my chair

while Huntley and Brinkley

gave us the news.

We heard their voices explain while

we saw on the screen the face of a long-haired girl

shouting and raising a fist.

The camera bobbled, moved,

focused on a boy lying face down,

moved again to students

screaming at soldiers whose guns pointed

at the camera. This time the war

not overseas, but in Ohio.

"I hope this trouble's over,"

my mother said,

"before you go off to college."

She had never said

I could go to college.

Kids from my town became

the soldiers, never the students.

What she said made my heart beat faster

but I never turned away

from the guns on the TV.

As I stared I thought

yes, yes.

On the screen I saw a way out.

The shooting and the panic

matched the anger in my hands,

matched the silent screams ringing in my ears,

screaming no against

those possible futures that I knew,

screaming yes

for the new, the unimagined.

I watched the distant college campus

on the little screen

and I longed fervently

for revolution.

In my first year of high school

my friends already talked

of marriage and children.

When they did I put my hands

over my ears.

A teacher told me

I'd never get a husband

if I didn't stop answering

all of the questions in class.

My friends talked of work.

I had no talent, like my mom,

for fixing hair.

And I was

too clumsy for a waitress

too sarcastic for a store clerk

too selfish for a nurse

too impatient for a factory line.

I was smart,

so I could be a secretary.

But restlessness ran in my veins--

I crossed my arms, clamped my jaw

and refused to learn how to type.

I didn't know what to dream of,

so I watched the news,

looking for a clue.

I wanted to see those places far from here

where there were wars.

I yearned for the rifle in my hands

but had to settle for shooting beebees

at popsicle sticks in the creek

while dreaming of being a boy,

joining the marines.

The TV seemed the only window

out of the living room walls.

My mother walked back and forth

while cooking dinner.

She paused

her worn hand resting

on the back of my chair

while Huntley and Brinkley

gave us the news.

We heard their voices explain while

we saw on the screen the face of a long-haired girl

shouting and raising a fist.

The camera bobbled, moved,

focused on a boy lying face down,

moved again to students

screaming at soldiers whose guns pointed

at the camera. This time the war

not overseas, but in Ohio.

"I hope this trouble's over,"

my mother said,

"before you go off to college."

She had never said

I could go to college.

Kids from my town became

the soldiers, never the students.

What she said made my heart beat faster

but I never turned away

from the guns on the TV.

As I stared I thought

yes, yes.

On the screen I saw a way out.

The shooting and the panic

matched the anger in my hands,

matched the silent screams ringing in my ears,

screaming no against

those possible futures that I knew,

screaming yes

for the new, the unimagined.

I watched the distant college campus

on the little screen

and I longed fervently

for revolution.